I wonder how I can begin to explain how much books

and reading mean to me. So many people have said it all before me and have said

it so much better than I ever could. I once read something written by W.

Somerset Maugham in which he expounds that there is nothing admirable about

admitting that you cannot go without reading:

|

|

'Of course to

read in this way is as reprehensible as doping, and I never cease to wonder at

the impertinence of great readers who, because they are such, look down on the

illiterate. From the standpoint of what eternity is it better to have read a

thousand books than to have ploughed a million furrows? Let us admit that

reading with us is just a drug that we cannot do without: who of this band does

not know the restlessness that attacks him when he has been severed from

reading too long, the apprehension and irritability, and the sigh of relief

which the sight of a printed page extracts from him? And so let us be no more

vainglorious than the poor slaves of the hypodermic needle or the pint-pot.' W Somerset Maugham

Admittedly not a terribly complimentary statement but there is an

element of truth there – I have to be able to read and the printed word (even

in electronic form) has always been, and will always be, a refuge for me: in

essence a drug, and no less addictive than a hypodermic filled with opiates.

I have been reading since I first began to

recognise the meanings of words. I was a bit of an introvert at school and added

to that I was not allowed to go out at weekends (good Portuguese girl and all

that) so I did not have many friends. How to fill the hours if not to read? No iPads,

no cell phones, not even any talking on the phone – a big, black, clunky thing

in the sitting room where the family gathered – and what was available on

television was laughable. It was all black and white at the time and my sister

and I weren’t allowed to watch many of the programmes (same reasons as for not

being allowed to go out). Fun, fun, fun!

With reading there was a limitless access to

material – school library and the library at the tennis club where my dad

played every weekend – it was private, I could travel to places I had never

been, and my social circle expanded exponentially. I loved it.

So it is a no brainer what my favourite subject at

school was … and because I was writing British exams (GCSE) there was a separate

subject called English Literature where I studied not one novel and one

Shakespeare along with some selected poetry, I was allowed to study ten more.

And then after all that I was still given a piece of paper in recognition of me

achievements. When I went to university it was even better: in my 1st

year English course we studied 22 books – the modern novel, Shakespeare, modern

theatre, African literature, Victorian novels and the entire works of Blake and

Yeats. Heaven indeed!

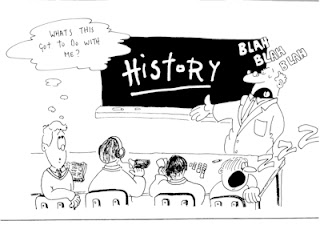

Small wonder then that I chose to teach English

(after that initial disaster where I taught History for one year). And I have

never tired of it. Imagine that, combining my two passions – reading and teaching

– and doing them every day.

Many of my students are resistant to studying

literature, poetry in particular – okay, I admit, most are reluctant – but that

becomes a challenge: to see if I can make even one of them change their mind. And

I often do and knowing that I have created a reader is an awesome feeling.

I seldom read fewer than three books a week: people

often ask how I find the time but it’s not a question of finding the time to

read, it is how I find the time to do anything else – it is all about

priorities after all.

I have learnt more from books and from reading than

I would ever have learnt in any other way. My insights into human nature, my

ability to understand sub text and to read between the lines, my awareness of

propaganda and when someone is trying to manipulate me, my insights into human

nature – all learnt through reading.

Carl Sagan was an American astronomer, cosmologist, astrophysicist, astrobiologist and author and was responsible for making science popular, even with philistines like me. This extraordinary man of science wrote:

'What an astonishing thing a book is. It's a flat object, made from a tree with flexible parts on which are printed lots of funny dark squiggles. But one glance at it and you're inside the mind of another person, maybe somebody dead for thousands of years. Across the millennia, an author is speaking clearly and silently inside your head, directly to you. Writing is perhaps the greatest of human inventions, binding together people who never knew each other, citizens of distant epochs. Books break the shackles of time. A book is proof that humans are capable of working magic.'

'What an astonishing thing a book is. It's a flat object, made from a tree with flexible parts on which are printed lots of funny dark squiggles. But one glance at it and you're inside the mind of another person, maybe somebody dead for thousands of years. Across the millennia, an author is speaking clearly and silently inside your head, directly to you. Writing is perhaps the greatest of human inventions, binding together people who never knew each other, citizens of distant epochs. Books break the shackles of time. A book is proof that humans are capable of working magic.'

I wholeheartedly agree.